## Hàn Thiếc Đơn Giản: Hướng Dẫn Cho Người Mới Bắt Đầu Hàn Qua Lỗ

Có lẽ bạn cũng đang ở cùng điểm trong hành trình sửa chữa của mình như tôi: Tôi biết cách sử dụng tua vít và dụng cụ bóc vỏ, đã tháo lắp rất nhiều dây cáp và thay thế không ít pin phồng. Nhưng mỗi khi gặp phải các mối hàn, những lời lẽ kinh khủng chống sửa chữa của các tập đoàn cứ văng vẳng trong đầu tôi: Hãy liên hệ với kỹ thuật viên được chứng nhận!

Quyết tâm vượt qua rào cản này, tôi quyết định tự mình giải quyết vấn đề. Tôi đã tìm kiếm lời khuyên từ các đồng nghiệp, xem

(Phần còn thiếu của bài báo)

Để hoàn thành bài viết, tôi cần phần còn lại của bài báo tiếng Anh. Vui lòng cung cấp phần tiếp theo để tôi có thể dịch và viết lại một cách đầy đủ và chuyên nghiệp. Sau khi bạn cung cấp, tôi sẽ bổ sung phần còn thiếu và thêm các hashtag phù hợp với nội dung.

Ví dụ về các hashtag có thể sử dụng (sau khi hoàn thành bài viết):

#hansua #hanthiec #dientu #sua chua #diy #handmade #hoc han #nguoi moi bat dau #cong nghe #elektronik #throughholesoldering #soldering #tutorial #beginner

Sau khi bạn cung cấp phần còn lại của bài báo, tôi sẽ hoàn thiện bài viết và thêm các hashtag phù hợp hơn.

Perhaps you’re at the same point in your repair journey as me: I know my way around a screwdriver and spudger, have popped many a cable and swapped my share of puffy batteries. But whenever I would come across soldered connections, the ghastly anti-repair corporate rhetoric swirled in my mind: Contact a certified technician!

Determined to overcome this barrier, I decided to take matters into my own hands. I sought advice from colleagues, watched instructional videos, explored forums, and even enrolled in a short primer class to boost my confidence and give me the basic knowledge to take the plunge. To document my journey and face down my fears, I chose to share my experiences in this blog.

While there’s a handful of soldering disciplines, this piece focuses on simple through-hole soldering. I’m going to go over my thought process setting up my workstation, then hop right into a through-hole soldering project.

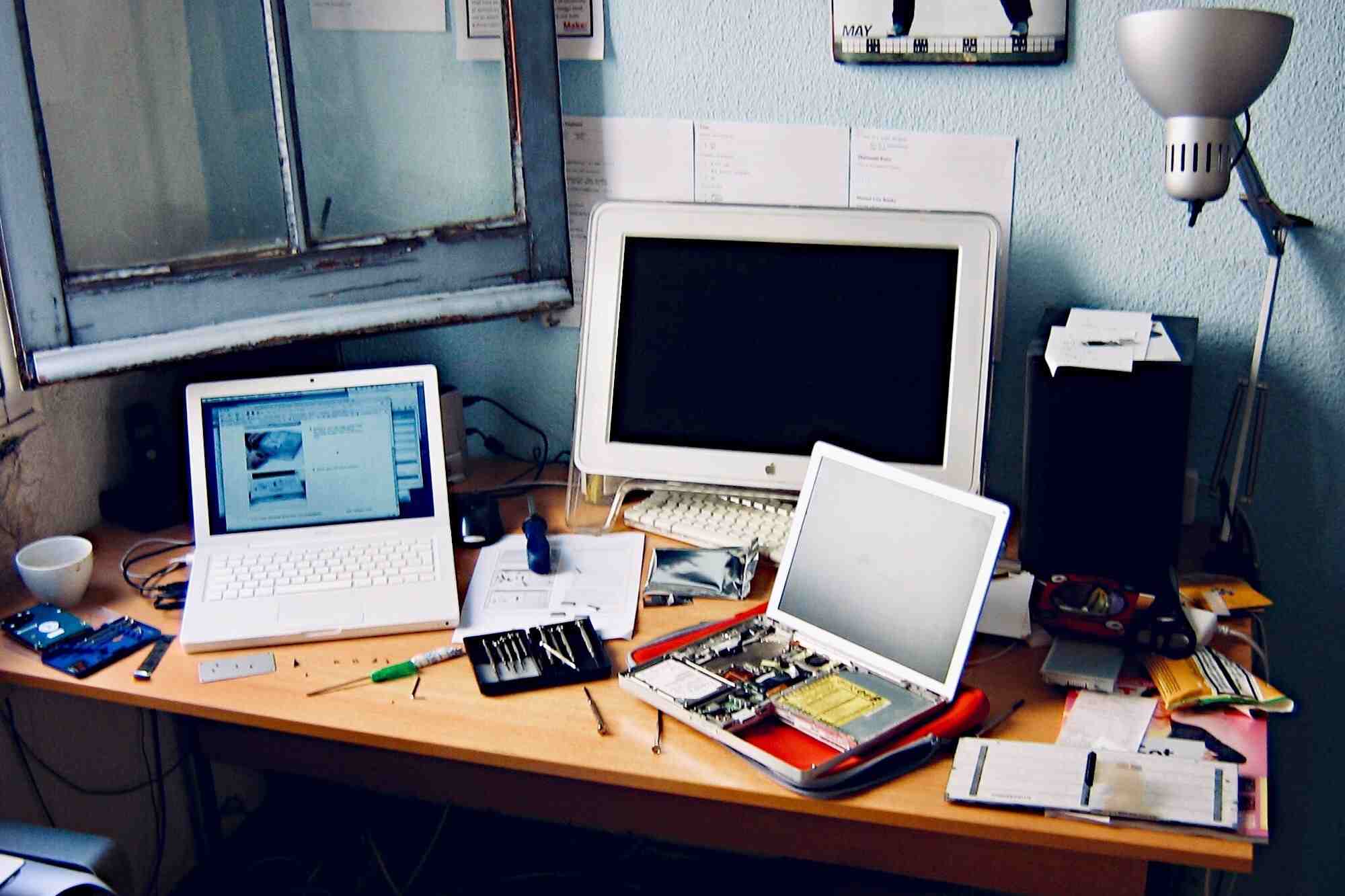

Setting Up My Workstation

There’s loads of soldering gadgets and doodads on the market, but I was interested in rounding up the basics so I could get right into soldering without any fluff! I was able to furnish my workstation with parts and tools scattered around the office, but I found that I could purchase all of the basics for around $100, and even less than $50 with secondhand shopping and a hint of creativity. (It’s also worth checking if your local tool library or community maker space provides soldering equipment!) Here’s the shortlist of the things on my workbench before I get into a bit more detail:

- Soldering station/tips

- Solder

- Tip cleaner (cleaning ball or sponge)

- Flux

- Solder wick

- Something to hold your project in place

- Flush cutters

- Fume mitigation

Soldering Station

The soldering iron is the magic wand for the modern electronic alchemist, turning solid metal molten!

There are plenty of budget-friendly, plug-and-play options that work in a pinch, but I would spring for a variable temperature iron that’s at least 60 watts—particularly if you plan on using lead-free solder, which I do. I found that being able to adjust the temperature on the fly and trusting the iron to hold a steady temperature is a huge help. I’m using a Hakko FX888D, in part because it’s a tried-and-true soldering station, but mostly because it was sitting in the office workshop.

Soldering Iron Tips

A soldering iron without a tip is like a pen without the nib—all the potential, but none of the point.

Lots of irons ship with a precise, conical point, but I found that the teeny tiny surface area on the tip seemed to struggle to maintain its set temperature. I found a smaller chisel tip to have more utility for through-hole soldering, at least for the relatively large pads on my project. I’m sure I’ll find more utility for different tips as I expand my soldering repertoire.

Tip Cleaner

The iron tips are awesome for conducting heat, but their conductivity is threatened by corrosion and buildup. The instructor of my soldering primer mentioned that keeping the tip free from gunk and buildup will improve its thermal conductivity and extend its lifetime dramatically. Most workstations come with a little sponge that you can dampen with distilled water and wipe the tip clean with, but I (and most solderers, it seems) prefer the little brass filing cleaning balls for three reasons:

- You don’t have to worry about keeping a sponge damp.

- Cleaning balls won’t reduce the tip temperature.

- Its abrasiveness tends to clean the tip more effectively.

Solder

Though many hobbyists prefer leaded solder due to its wettability and lower melting point, I’m using lead-free solder. Even though an iron shouldn’t be getting hot enough to release lead particles into the air, I don’t like the idea of handling lead one bit—it’s, uh, not great for you. Lead in e-waste is also a massive safety issue for recyclers and the environment.

After looking at forums debating leaded vs. lead-free solder, I encountered a baffling amount of hate for lead-free solder. To be honest, I found a lot of that to be hyperbole. With a solid iron and proper preparation, lead-free solder is a breeze to work with. It’s definitely more expensive, but a decent spool is going to last me for a long time!

Flux

Aside from a functional iron and solder, many folks insist that flux is one of the most critical elements of anyone’s soldering toolbox. Flux is a mildly acidic solution that cleans the contact points, removes oxidation, and helps solder flow. Most solders already have a flux core, but I always ended up needing a little more.

For through-hole soldering, I was advised to use rosin-based flux. I used a flux pen my first time soldering, and it was convenient and very easy to apply. For this project, though, I ended up using a no-clean tack flux syringe with a precise tip because a generous colleague had some handy. To learn more about flux and to help decide which type is best for your use case, check out this helpful article.

Solder Wick

Accidents happen, and while soldering feels indelible, desoldering is possible! I made a pretty major soldering slip-up later in the article (keep reading to hear all about it), and found solder wick to be an invaluable tool to mop up my mistakes. I tried to use a desoldering pump, which sucks up molten solder like a straw but didn’t find much success. However, I’ve seen some videos of people using desoldering pumps with excellent results, so I suspect my failure was a skill issue!

Flush Cutter

This doesn’t fall in the strictly necessary category, but flush cutters are useful for trimming off the protruding component legs after being soldered into place. In a pinch, I’d bet most smaller wire cutters will do the job, so long as a little extra leg sticking out of the joint isn’t an issue.

Something to Hold Your Project in Place

Some solderers prefer helping hands or fancy jigs, but I used a strip of masking tape to hold the board in place. It’s super low-cost and works just fine!

Okay, almost to the fun part! One last, really important note, though.

Boring But Important: Safety!

As stoked as I was to get right into it, the old adage rang in my head: Safety First!

To venture a wild guess, working with molten metal may have some inherent dangers, so I did a little homework and compiled a short safety checklist. Here are a few safety tenets I pledged to follow at my workstation:

- I’ve got long hair, so I tied it up and out of the way. If you’ve got a wizardly beard (no, I’m not jealous at all, I can totally grow one) keep it out of harm’s way.

- Move away any flammable objects. Although a successful project inevitably brings tears of joy, I keep my tissues well out of reach while the iron’s hot.

- Be sure to work on solid, flame-resistant surfaces. I’m lucky to have a solid wood table to work on, but a silicone mat to solder on top of is on my wish list.

- Molten metal securing components=awesome. Molten metal in my eye=my childhood dream of being a pirate realized! I wear glasses, which will do the job of protecting the ol’ optics. Throw on something to protect your eyes.

- Whenever I’m not actively soldering, or if I get up for a bathroom break, I switch the iron “off.” It’s a no-brainer to avoid leaving a hot iron unattended.

Fume Extraction

If D.A.R.E. taught me anything, it’s that a good rule of thumb is not to inhale smoke of any kind—and that’s certainly true when it comes to soldering fumes. When soldering, the visible smoke is mostly vaporized flux, which irritates lungs and can cause all sorts of nasty ailments with prolonged exposure. In short, soldering fumes just don’t belong in lungs, so I am taking some precautions to avoid fume inhalation.

There are plenty of extremely expensive, ultra-effective fume extractors on the market, but they’re a bit overkill for the average hobbyist like me who has relatively low exposure rates and doesn’t plan on making soldering my profession.

I’m using a simple, relatively inexpensive smoke extractor that will arrest and disperse some of the fumes. A way more fun and cost-effective option is building your own!

However, since the filter media in the extractor I’m using is somewhat porous activated carbon, I’m not trusting it to remove the majority of the fumes/particles—so I’m ventilating my workspace, too. In the future, I might rig up a simple computer fan attached to a tube that ports straight outside (something like this) to prevent fumes from lingering in my workspace altogether. Some might call me paranoid, but basic fume mitigation will probably cost less than a single doctor visit.

TL;DR: Find a way to not inhale soldering fumes!

Lastly, after soldering, I’m washing my hands thoroughly—even though I’m using lead-free solder. That goes doubly, triply, perhaps quadruply if I end up using leaded solder and/or working on older electronics; older electronics usually contain gobs of lead. Although leaded solder is mostly phased out in modern consumer electronics, I’m going to stay on the safe side and assume that any boards I handle contain lead.

Start Your Engines!

I’ve got my workstation set up, windows are open, and the fume extractor is spun up! Let’s lay down some metal! Wait… what am I soldering again?

I’m starting out with a straightforward through-hole kit, just to warm up—my iron, that is. Through-hole soldering involves inserting component leads into pre-drilled holes on a printed circuit board (PCB) and soldering them on the opposite side.

I decided to start out with a little through-hole kit for a few reasons:

- The instructions are straightforward, and the size of the pads are pretty generous.

- I’ll know relatively quickly if I’ve messed up or not. I know that disassembling, desoldering, resoldering, and reassembling a more complex project would be crushing sans a satisfying power-up at the end of the silver-joint road.

- If you mess up past the point of no return, you’re only out as much as the kit cost, which generally ain’t much.

I’m using the Angry Storm Cloud from Alpenglow Industries, but similar kits are all over the place. It doesn’t do a whole lot when completed, aside from lighting up some pretty LEDs to show that the circuit is complete and that the joints are capable of conducting a current.

Heat the Iron and Tin the Tip

A cold soldering iron is as useless as a pogo stick in quicksand, so I gotta heat it up! Somewhere around 400C (750F) is the general rule of thumb for lead-free soldering. I was having some issues with liquefying the solder at that temperature, so I bumped it up to around 425C (800F) and found my solder much more willing to go with the flow.

After the iron was heated, I cleaned off the tip with a ball o’ brass, then tinned the tip. Tinning the tip is the process of coating the tip with a thin layer of solder, which helps to preserve the tip and improve heat conductivity. Soldering is the name, but heat transfer is the game.

Secure the Component; Secure the Board!

With the iron hot and raring for action, I decided in a split-second that the first component going in was the switch—luckily, the instructions mirrored my primal instincts! I pushed the leads through the marked holes, then took a small strip of masking tape and secured the switch flush against the board. I then flipped the board around and taped the whole thing down to my work surface with the leads facing up.

Though I’d love to check out some other jigs on the market, I found that simply taping the project down allowed me to hold the iron naturally, like a pencil, with my hand resting against the work surface for extra stability. Masking tape is ideal because it’s designed to leave minimal residue.

Flux It Up!

Before grabbing the solder, I dabbed some flux on the copper pads, and a bit on the leads too. I was a little messy with the flux, but that’s no big deal. After I’m done soldering, I’ll just take a lint-free cloth damp with high-concentration isopropyl alcohol and clean it up. No-clean flux (a definite misnomer), which I’m using, is relatively non-corrosive—so it’s really not the end of the world if some rogue flux ends up on the board. I’d rather have more flux than I need than not enough!

After somewhat messily fluxing the copper pads and leads, the moment of truth arrived: Do I have the mettle to lay down the metal?

Soldering the Switch

With the switch fluxed and secured, I grabbed the hot iron with my right hand, and the spool of solder with my left. I touched the iron tip to both the lead and the copper pad, gave it a moment, then fed in some solder from the other side. A quick note: Be sure to touch the iron to both the lead and the copper pad—or whatever surfaces that you want to join. This is really important, as both surfaces need to be hot in order to form a proper connection. If the surfaces are not well-heated, you’ll create a poor connection, or the solder will ball up on the component lead instead of encapsulating the lead.

After the solder liquified and pooled around the joint, I pulled the solder spool away and left the iron on a moment longer to ensure that the solder flowed around the entire joint. If you lift away the iron first, you also run the risk of cementing your whole spool of solder to the joint! Once everything was properly flowed, I pulled the iron away, and voilà! A conductive joint has been forged. Before I started on the next connection, I gave the iron tip a good wipe or two on the cleaning ball to keep oxidation and buildup at bay.

All in all, the connections looked pretty good! Definitely not perfect, or particularly pretty, but the sight of (probably) conductive joints filled me with a hot-slag-surge of satisfaction! In the future, I might try to add a tad more solder to create a smoother, more concave slope—I’m thinking cartoon volcano!

Next up, the glowing LEDs.

LEDs Inbound!

With the switch secure, next to join the circuit family are a set of three LEDs (Light Emitting Diodes). Whereas the switch had short, thicker leads, LEDs have two long, spindly legs, one an anode (+) and one a cathode (-).

I inserted the LEDs flush to the board, with care to ensure that I inserted the anodes and cathodes through the correct holes, then bent them a bit to hold them in place. Don’t bend the legs too much, as it makes it harder for the solder to flow around the entire pad.

I followed the same procedure as the switch and was pretty happy with how the joints looked, aside from them looking a bit bulbous. When it comes to soldering, sometimes less is more.

I went ahead and snipped off the protruding legs with a flush cutter. Holding the lead while snipping to avoid sending metal flying across the room is recommended. Anyone in the room—and your vacuum cleaner—will thank you.

I thought I was in good shape, ready to move on to the final component. However, after taking a look at my work, I realized that I made a monumental mistake. I was laser-focused on soldering, but not so much on making sure that I inserted the LEDs from the correct side. In an embarrassing display of tunnel vision, I violated the soldering equivalent of the sacred “measure twice, cut once” adage.

Now, technically, I could’ve soldiered on and the LEDs would still light up just fine—even if they were facing the wrong direction. But what better time to learn how to desolder!

Desoldering: A Totally Intentional Demonstration

I first took a length of some copper wick and put some flux on it to help the liquid solder draw into the wick, like a little copper sponge. Brillo pads wish they had a fraction of this power!

With the iron hot, I placed the wick on top of the joint, then applied light downward pressure with the iron tip. It was a bit of a challenge to remove enough of the solder to free the LEDs, but changing the angle and trimming the wick when it became saturated sped up the process. If you encounter trouble, applying more flux to the joint can help the solder flow into the wick. With the majority of the solder pulled into the copper crevices of the wick, the LEDs were (mostly) free!

All that was left was to work the leads straight, then I simply pulled them right out! While desoldering is definitely possible, and a necessary skill, I strongly recommend soldering your components correctly the first time.

Since I’d already trimmed off the legs of the LEDs, I had to tape them in place before soldering them in the correct orientation. With the LEDs oriented and secured in the proper direction, all that’s left is the battery terminal. A quick tape, a couple dots of solder on the stormcloud “eyes,” and let there be light! Before I put the iron away, I gave it a good brush on the cleaning ball, then tinned the tip once more.

Now, for a moment of reflection.

How’d I Do?

Taking a look over the joints, the quality varies quite a bit. The switch leads aren’t terrible, but are lacking a bit of solder and don’t slope up quite like I’d prefer to see.

The LED connections are a bit blobby, and might threaten to bridge if I added even a hint more solder in some places.

My joints are nothing to write home about, but I made the LEDs light up, and for now, that’s good enough for me! Not to mention, they look a whole heck of a lot better than my first project, which I will show you; you may want to take a deep breath and sit down.

Egad! Relatively speaking, I think I did just fine this time around, especially when comparing it to my first try—although looking at those joints, maybe that ain’t saying much.

Final Thoughts

For me, there was a certain mystique around soldering that lifted further with each shiny joint: Before I started, soldering seemed dangerous and prohibitively complex. I mean, it’s not not dangerous, but we’re also not working with gunpowder; and it’s not as simple as turning a screw, but it also ain’t rocket science. Well, some soldering is rocket science, but that’s beside the point!

Soldering isn’t just reserved for the pros, and with the right equipment and a can-do attitude, I believe anyone can get good enough to step up their repair and DIY game and make their soldering dreams come true. Yeah, my connections aren’t meeting any IPC standards, but the dang LEDs are lighting up!

So, grab a soldering iron, take a deep breath, and dive in—you’ll be amazed at what you can create with a bit of practice and patience. Soldering is for both the pros and the average joes!

Source link [featured_image]